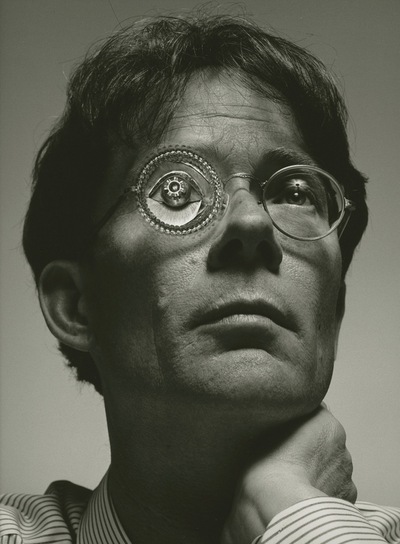

William Gibson Interviewed back in the 1990s by Jeffrey Goldsmith

William Gibson wrote the only sci-fi novel ever to win the Hugo, Nebula and Philip K. Dick Awards – Neuromancer – thereby definitively establishing a subgenre. Cyberpunk.

Before this world of techno dirt yet had a name, Mr. Gibson went to the movies, to Blade Runner. Atmospherically, the film evoked so much of what he was trying to do.

His gun had been jumped, but rather than finding it depressing, he kept at it, bringing us the story collection, Burning Chrome, the triple award winning Neuromancer, then the follow up works, Count Zero, Mona Lisa Overdrive, Virtual Light and Idoru.

A cool hack.

JG: You and I are 2943 miles from one another, talking on the telephone. Alexander Bell probably freaked out just listening in the other room.

WG: It’s all quite relative. Consequently I haven’t come reeling out of anything gasping, “My God! What an astonishing experience that was!”

JG: We might never. It might all come so slowly that we get used to it as it comes.

WG: My hunch is that all of that stuff, the goggles, the machines, all those machines we’ve been seeing in Sunday Supplements for the last several years, in 50 years will look like the funny machines that preceded film. Like the Panakinoscope, the scarcely remember intermediate stage between forms of media, a miniature, tabletop merry-go-round with a window you look through. You turned a crank and you saw horses running. All the VR glasses are going to look to people the way that stuff looks to us.

JG: Do you think it’s true that film is just a transition stage to what you call simstim, simulated stimulation?

WG: It’s true in a sense, but I think it goes back even further. If you read the accounts of the first people who went on railroads in England and Europe, their descriptions of what it was like to go 10 miles an hour were quite intense and hallucinatory. Really, really strange experience for them. I think far stranger for them than for us to go into VR simulation. People screamed and ran out of theaters when they were shown silent films of trains rushing at them. It took a while for people to get used to it.

JG: Did they think it was real?

WG: They just didn’t know how to react. It wasn’t that they thought it was real, but they just didn’t know what was going to happen. I don’t know if that could ever happen to us. That’s the intensity of experience people building VR equipment are striving to get.

JG: I almost think we’re jaded by technology, that we’re so used to NEW!, how could someone give us something that would blow our minds?

WG: I think the last time anybody gave us anything like that was Sony’s invention of the Walkman. The first Walkman was a breathtaking experience.

JG: But why do you think people want simstim. Why do you think we crave that?

WG: I don’t crave it at all. For me it was just a metaphor for contemporary media. It was a way to deconstruct media. To the arrival of an industry predicated on realizing that fantasy, my response has been pretty ironic, by and large. Peculiar to meet people trying to figure out ways to duplicate it.

JG: Simstim also causes people pain.

WG: It’s problematic, but television isn’t something that just makes you feel good.

JG: What else does television do?

WG: It does a lot of weird things to me, but making me feel good is something it hardly ever does. All that imagery for me was a way of pushing back at media. It gives me something to shove back with, which would be very hard to do if I was just writing about people watching CNN and MTV. It’s easier for me to convert it all into sci-fi and having these people plug TV directly into their necks, which you don’t have to do. Get up to a big television and turn it up really loud. You can quite get lost in it.

JG: A linguist friend of mine once commented that television has transformed our worldview. I can turn mine on and watch cruise missiles in the night sky over Baghdad, live. Then I can change the channel to a gameshow and sedate myself. What can you do about that?

WG: To the extant that my work is subversive, it sometimes makes people realize how unthinkably weird the world we live in is. It’s not as though we live in a “normal” world, whatever that would be. We live in a world of unthinkable weirdness that’s headed towards greater weirdness. And there’s not too much you can do about that except, you know, listen up. Be aware of it, otherwise it’s all wasted on you. You’ve got to be aware to appreciate this shit for it’s full strange postmodern value. The only thing I can think of to do these day is just try to spread your mind and resonate with how strange things are getting.

JG: That seems like the most natural thing to do.

WG: One guy argued with me very passionately that for the most part things were pretty much the way they were in the 50’s. So there we were in my backyard surrounded by rosebushes and robins and he’s saying, “Look at this place. This could be Leave It To Beaver.” I said, “Well, there are measurable amounts of isotopes from the Chernoble reactor in these rosebushes.” There are.

JG: Allen Ginsberg once told me the world is going to end up like some kind of “molasses.”

WG (laughs): The world today is like city planning in Mexico City. Mexico City has city planners and they really are quite a heroic bunch. What they’ve been doing is dealing with flat out, total emergency for decades and they don’t anticipate that it’s going to get any “better”, but they continue to try to make parts of it more livable when possible. They just try to deal with this vast, entropic system. When I look at that I think, “Maybe that’s what the future is going to be like.” The really creepy thing is there are a couple of places around that have attained a kind of order, high tech organizations that right wing sci-fi writers in the fifties thought would be a good future for America. Places like Singapore.

JG: Which is boring as hell.

WG: They have all this stuff which on the face of it is quite admirable which you could easily imagine being implemented in places like Portland.

JG: $500 fines for littering.

WG: It’s very, very clean, but it’s astonishingly boring.

JG: In the trilogy, there’s a great deal of Tokyo.

WG: I wrote those first three books never having gone there.

JG: Did you ever have hot coffee in a can for 100 Yen?

WG: I had a funny experience with that. The first fifteen minutes I was in Tokyo I got a can of that coffee at the minimart in the hotel and had my first experience with this iced, canned coffee. Then I went out walking in the street and it was a very hot, sunny day and I saw this coffee machine and so I said, “Oh! Iced coffee from a machine.”

JG: You pressed the red button.

WG: Yeah. I reached in and burned my fingers. Microwaved the can. They have some weird stuff in vending machines.

JG: Not VR glasses, yet. Tell me about virtual light – images direct to the brain. What fascinated you about the idea?

WG: It doesn’t take a high degree of fascination to find its way into my books. I just thought it was a cool hack. It’s an interesting way around the isolation of the goggles kind of VR. With a Virtual Light rig you can see VR artifacts in your real setting. Mickey Mouse can come into your apartment and sit on your couch, talk to you, interact with you, like the holograms in Wild Palms.

JG: You were in that – the man who coined the phrase cyberspace – and you said, “They’ll never let me live it down.” How did you end up in that?

WG: Bruce Wagner is a friend of mine. It was a favor both ways. He wanted me to do it an I thought it was cool to do. I’d always liked the script, which I had read in various stages. By and large I thought the realization was pretty good.

JG: Can you define cyberspace?

WG: That’s a really hard question to answer these days because when I came up with it in Burning Chrome I used it to define a kind of navigable, iconic, three dimensional representation of data. That still is one definition, but there are also six other definitions that have subsequently been attached to it by people working in computer modeling. So it now has technical definitions, which are in some cases beyond my understanding.

JG: But isn’t even reality cyberspace? A table is an iconic of representation of data. You can sit and eat at it. So cyberspace becomes a metaphor for the real world.

WG: In my work it became a metaphor for all kind of things. In those three books I undertook basically without planning to initially, an encyclopedic investigation of its metaphoric possibilities. So in those three books there are god knows how many kinds of cyberspace described, but there is also the sense the physical world is something like that. There are points where it becomes quite peculiar philosophically. Those are some of my favorite bits in those books, where you feel like you’re not quite sure if they’re in the construct or they’re in the real world. Which is which?

JG: What’s your ideal reader?

WG: My ideal reader would get pleasure from having their expectations messed with, as opposed to getting a generic shot of William Gibson. There are a lot of things that seem to be quite familiar riffs, which turn out to be inverted.

JG: Is inversion a moniker of cyberpunk?

WG: I could write Christian Exit Jesus and they’d still put cyberpunk on my tombstone.

JG: Sorry I labelled you. It must suck, but does this mean you are going on to something else?

WG: I’m not sure. I’m certainly not going to go back and write William Gibson’s Cyberspace 4 – The Adventures of Young Molly. No, sorry. I’m not going to do that, but I’m in transition. I would hesitate to say into what.

JG: No, you have to write it to find out what you’re “transitioning” into.

WG: I really do. I have to write it to find out what it is. One thing I think I do have in common with Elmore Leonard is that I don’t like to know the ending when I start. If I can’t go along for the ride it becomes….

JG: Boring?

WG: Very boring. So it’s an exploratory process.

JG: Give me an example.

WG: The unemployed cop turns out to be not a glamorous law figure, but the boy next door and that’s an inversion. The only character in the book that’s wired like the characters in Neuromancer is Loveless, who is clearly this flat-out, psychotic, contract killer. If Loveless did a walk on in Neuromancer none of the other characters in would notice him. Neuromancer is filled with flat-out, psychotic, contract killers, but it seems to be taken for granted. [Virtual Light] is not a world of Clint Eastwood spaghetti westerns, which was what a lot of my earlier work was supposed to be. That was the intended feeling.

JG: Loveless kept coming in with the same, mean smile.

WG: He’s very much like an early Gibson character. The part where he’s been slipped too much dancer and starts pounding himself in the crotch with an automatic piston is one of my favorite bits in the book.

JG: I recently read claims by computer hackers that they were doing the stuff while you were writing Neuromancer.

WG: I had no idea anybody was actually thinking about doing that stuff. It came as a complete surprise to me, but I thought it would happen anyway just as a synthesis of tv and computers. Everything else we’ve been doing since WW2 has been going in the direction.

JG: The first audiences marvelled at movies….

trans to simulated stimulation. Do you think that’s true.

WG: It’s true in a sence, but I think it goes back even further. If you read the accounts of the first people who went on railroads in England and Europe, their descriptions of what it was like to go on a railroad going 10 miles an hour were quite intense and hallucinatory. Really, really strange experience for them. I think far stranger for them than for us to go into VPL simulation.

JG: We’re 2934 … Bell probably freaked out just listening in the other room.

WG: It’s alll quite relative and consequently I’ don’t find any of the existing VR equipment I’ve tried, particualary… I haven’t come realing out of anything gasping, “My God! What an astonishing experience that was!”

JG: We might never. It might all come so slowly that we get used to it as it comes.

WG: My hunch is that all of that stuff, the goggles, the machines, all those machines we’ve been seeing in Sunday Supplements for the last several years, in 50 years will look like the funny machines that preceaded film. Like the Panakinoscope, the scarscly remember intermediate stage between forms of media. One of hundreds of patented gizmos to show you moving pictures. A minerature, tabletop merrygoround with a window you look through. You turned a crank and you saw horses running. All the VR The VR glases are going to look to people the way that stuff looks to us.

JG: Lumieri’s Man who went to the Moon.

WG: People screamed and ran out of theaters when they were shown silent films of trains rushing at them. It took a while for people to get used to it.

JG: Did they think it was real?

WG: They just didn’t know how to react. It wasn’t that they thought it was real, but they just didn’t know what was going to happen. I don’t know if that could ever happen to us. That’s the intesity of experience people building VR equipement are striving to get.

JG: I almost think were jaded by technology, that we’re so used to NEW!, how could someone give us something that would blow our minds?

WG: I think the last time anybody gave us anything like that was Sony’s invention of the Walkman. The first Walkman was a breathtaking experience. Fax machines are a pretty good hack.

JG: Why do you think people want SimStim. Why do you think we crave that?

WG: I don’t crave it at all. For me it was just a metaphore for contemporary media. For me it was a way to deconstruct media and the arrival of an industry predicated on realizing that fantasy, my responce has been pretty ironic by and large. It realy isn’t something I lie awake yerning for. Peculiar to meet people trying to figure out ways to duplicate it.

JG: In the trilogy, there’s a great deal of Tokyo.

WG: I wrote those first three books never having gone there.

JG: Did you ever have hot coffee in a can for 100 Yen?

WG: I had a funny experience with that. The first fifteen minutes I was in Tokyo I got a can of that coffee at the minimart in the hotel and had my first experience with this iced, canned coffee. Then I went out walking in the street and it was a very hot, sunny day and I saw this coffee machine and so I said, “Oh! Iced coffee from a machine.”

JG: You pressed the red button.

WG: Yeah. I reached in and burned my fingers. Microwaved the can. They have some weird stuff in vending machines. They have something called ‘Nutriblok’, this generic protein.

JG: Straight out of 2001. Blue food. I’m stuck on this idea of SimStim. It causes people pain.

WG: It’s problematic, but television isn’t something that just makes you feel good.

JG: What else does television do?

WG: It does a lot of weird things to me, but making me feel good is something it hardly ever does. All that imagery for me was a way of pushing back at media. It gives me something to shove back with, which would be very hard to do if I was just writing about people watching CNN and MTV. It’s easier for me to convert it all into sci-fi and having these people plug tv directly into their necks, which you don’t have to do. Get up to a big television and turn it up really loud. You can quite get lost in it.

JG: Tv worldview

If you’re trying to fight it, you’re being very subtle.

WG: I want people to be aware of it. To the extant that my work is subversive, in that it sometimes makes people realize how unthinkably weird the world we live in is. It’s not as though we live in a “normal” world, whatever that would be. It’s headed towards great weirdness. We live in a world of unthinkable weirdness that’s headed towards greater weirdness. And there’s not too much you can do about that except, you know, listen up. Be aware of it, otherwise it’s all wasted on you. You got to be aware to appreciate this shit for it’s full strange postmodern value. The only thing I can think of to do these day is just try to spread your mind and resonate with how strange things are getting.

JG: I can’t think of anything more useful or less useful or more natural. That seems like the most natural thing to do.

WG: One guy argued with me very passionately that for the most part things were pretty much the way they were in the 50s. So they we were in my backyard surrounded by rosebushes and robins and he’s saying, “Look at this place. This could be Leave It To Beaver.” I said, “Well, there are measurable amounts of isotopes from the Chernoble reactor in these rosebushes.” There are.

JG: Allen Ginsberg old me the world is going to end up like some kind of “mollassas.”

WG (laughs): The world today is like city planning in Mexico City. Mexico City has ciry planners and they really are quite a heroic bunch. What they’ve been doing is dealing with flat out, total emergency for decades and they don’t anticipate that it’s going to get any “better”, but they continue to try to make parts of it more livable when possible. They just try to deal with this vast, entropic system. When I look at that I think, “Maybe that’s what the future is going to be like.” The really creepy thing is there are a couple of places around that have attained a kind of order, high tech organizationms that right wing sci-fi writers in the fifties thought would be a good future for America. Places like Sinapore.

JG: Which is boring as hell.

WG: They have all this stuff which on the face of it is quite admirable which you could easily imagine being implimanted in places like Portland.

JG: $500 fines for littering.

WG: It’s very, very clean, but it’s astonishingly boring.

JG: Tell me about Virtual …. what

WG: It doesn’t take a high degree of facination to find it’s way into my books. I just thought it was a cool hack. It’s an interesting way around the isolation of the goggles kind of VR. With a Virtual Light rig you can see VR artifacts in your real setting. Mickey Mouse can come into your apartment and sit on your couch, talk to you, interact with you, like the holograms in Wild Palms.

JG: You were in that. The man who coined the phrase cyberspace and you said, “They’ll never let me live it down.” How did you end up in that?

WG: Bruce Wagner is a friend of mine. It was a favor both ways. He wanted me to do it an I thought it was cool to do. I’d always liked the script, which I had read in various stages. By and large I thought the realization was pretty good.

JG: Speaking I’ve heard your working on a script.

WG: I’m working on another draft of a screenplay that I did last year for Robert Longo’s feature of a story of mine called Johnny Mnemonic, which is getting closer to being something that actually may be filmed.

JG: I’ve read Johnny Mnemonic. He rents out brain space.

WG: He’s a cross between a mule and a stashbox. You hide stuff in him. He doesn’t have any acess, conciously.

JG: Crime… Leaonard.

WG: I have read Elmore Leanard all my life. Yeah, this is very conciously at one level envisioned as something like an Elmore Leonard novel set in the very near future. If there could be such a thing. it’s also a delibarate deconstruction of a lot of my previous work. It’s like an Elmore Leonard novel with some really sneaky postmodern agenda running in the background. Some people got it.

JG: What’s your ideal reader.

WG: My ideal reader would get pleasure from having their expections messed with, as opposed to getting a generic shot of William Gibson. There are a lot of things that seem to be quite familiar riffs, which turn out to be inverted.

JG: Give me an example.

WG: The unemployed cop turns out to be not a glamerous law figure, but the boy next door and that’s an inversion. The only character in the book that’s wired like the characters in Neuromancer is Loveless, who is clearly this flat out psychoitc contract killer. If Loveless did a walk on in Neuromancer none of the other characters in Neuromancer would notice him. Neuromancer is filled with flat out, psychotic contract killers, but it seems to be taken for granted. [Virtual Light] is not a world of Clint Eastwood spaghetti westerns, which was what a lot of my earlier work was supposed to be. That was the intended feeling.

JG: Loveless kept coming in with the same, mean smile.

WG: He’s very much like an early Gibson character. The part where he’s been slipped too much dancer and starts pounding himself in the crotch with an automatic piston is one of my favorite bits in the book.

JG: Mine, too. He’s already completely supressed, why not just mash it. Is this how cyberpunks end it?

WG: I could write Chirstian Exit Jesus and they’d still put cyberpunk on my tombstone.

JG: Sorry I used the label. It must suck. One last question, a heavy one. Can you define cyberspace?

WG: That’s a really hard question to answer these days because when I came up with it in Burning Chrome I used it to define a kind of navigable, iconic, three dimensianol representation of data. That still is one definition, but there are also six other definitions that have subsequently been attached to it by people working in computer modeling. So it now has technicle definitions, which are in some cases beyond my understaning.

JG: But isn’t even reality cyberspace? A table is an iconic of representation of data. You can sit and eat at it. So cyberspace becomes a metaphore for the real world.

WG: In my work it became a metaphore for all kind of things. In those three books I undertook basically without planning to initially, an encylopedic investigation of its metaphoric possibilities. So in those three books there are god knows how many kinds of cyberspace described, but there is also the sense the physical world is something like that. There are points where it becomes quite peculiar philosophically. Those are some of my favorite bits in those books, where you feel like you’re not quite sure if they’re in the construct or they’re in the real world. Which is which?

JG: Sometimes I wonder that myself just sitting here. So you are going on to something else?

WG: I’m not sure. I’m certainly not going to go back and write William Gibson’s Cyberspace 4 – The Adventures of Young Molly. No, sorry. I’m not going to do that, but I think Virtual Light is a transition into something. I would hesitate to say what.

JG: No, you have to write it to find out what you’re “transitioning” into.

WG: I really do. I have to write it to find out what it is. One thing I think I do have in common with Elmore Leonard is that I don’t like to know the ending when I start. If I can’t go along for the ride it becomes….

JG: Boring?

WG: Very boring. So it’s an exploratory process.